Step inside the kaleidoscopic universe of Pipilotti Rist

Swiss artist Pipilotti Rist, who headlines Wallpaper’s November 2022 issue, has transformed the way we see, with a poetic yet playful practice spanning three decades. Here, and in a special portfolio, she reveals how she has liberated video art from its conventions, imbued the digital realm with emotion, animated public spaces, and harnessed the healing powers of colour

- (opens in new tab)

- (opens in new tab)

- (opens in new tab)

- Sign up to our newsletter Newsletter

A bodiless voice with a singsong Swiss lilt rings forth. After a few seconds of staring into the Zoom void, a wonderful burst of colour explodes onto the screen as Pipilotti Rist materialises in virtual form from her studio in Zurich. Much like her immersive video installations, the Swiss artist seems incapable of being confined to pixels: her ebullient character is magnified by the polka dot apron she is wearing. A colourful crochet blanket draped over the orange chair next to her completes the richly polychromatic picture.

When we speak in late August 2022, Rist has just returned from a six-week sojourn in Hong Kong installing her major solo show, ‘Behind Your Eyelid’, at Tai Kwun, a former police station-turned-cultural destination in the city’s Central district. Her heady installations sprawl beyond the confines of the Herzog & de Meuron-designed galleries, blanketing the complex’s courtyards and appearing on unlikely surfaces, such as a barred window. ‘My work is about freeing the electronic image from its square and bringing it into the physical realm,’ says Rist. Curated by Tobias Berger, head of arts at Tai Kwun, the survey spans Rist’s three-decade-long practice, from earlier mono-channel videos such as Sip My Ocean (1996) and Ever Is Over All (1997) to site-specific installations. There’s an iteration of Pixel Forest: a hypnotic tangle of LED lights, each distinct like crystals (or ‘frozen labias’, as the artist cheekily notes in the catalogue). Elsewhere, Omvendt øjenlåg (Reverse Eyelid) (2022), originally created in collaboration with Danish textile brand Kvadrat, has been reimagined, while Big Skin is a sensorial environment combining real footage with 3D animation.

‘Pipilotti’s art lets us see things that we should but don’t, because we don’t look close enough,’ says Berger. There’s an Alice in Wonderland perspective to the show as the artist supersizes macro details – such as the intricate veins of a plant – on suspended screens, or projects a coin-sized video on the floor, compelling the audience to consider a new spatial language. Berger adds, ‘What you don’t necessarily realise when you see her work is just how precise she is, not just with every colour and pixel, but also with the equipment. She always pushes to get more out of the equipment than anybody ever thought possible. The word I hear a lot is: “dream”. But you do not dream about computer-generated images, you dream about reality. That is what is so beautiful about Pipilotti’s work: this surprise of the “real”.’

Born Elisabeth Charlotte Rist (Pipilotti is a portmanteau of Rist’s childhood nickname and Astrid Lindgren’s literary heroine Pippi Longstocking) in 1962, the artist is the second of five siblings (her younger sister, Tamara, is a seamstress who regularly creates textiles for Pipilotti’s installations). Her late father, the son of a baker, was a doctor; her mother, the daughter of a farmer, is a teacher. From the villages in the canton of St Gallen where she was raised, Rist found a portal to music and popular culture through mass media – Yoko Ono, in particular, resonated with her. ‘For many people, including myself, it was an entrance into a world that I would not have known,’ the artist says. ‘In the 20th century, our biographies were not defined by birth anymore. That was a big development, and it started with my parents’ generation.’

Rist’s journey to video art was serendipitous: she initially used Super 8 film to create stage effects and images to be projected during concerts for local musical acts such as Billion Bob and all-female group Les Reines Prochaines. ‘I wanted to be in service of the music,’ explains Rist. ‘In a way, I am still creating music stages – except instead of a band, there are visitors.’ Music continues to play a role in her practice today: ‘Though my tendency is to look more at the image, I pay heavy attention to sound so that it is not neglected,’ she says.

After graduating in 1986 from the Institute of Applied Arts in Vienna, the 24-year-old Rist returned to Switzerland and enrolled at the School of Design in Basel, where she studied under Swiss artist René Pulfer. During her first year of video studies, the artist submitted I’m Not The Girl Who Misses Much (1986) to the Solothurn Film Festival – the seven-minute video was eventually placed into a group exhibition at Basel’s Museum of Applied Arts. Rist has exhibited at the Venice Biennale and São Paulo Art Biennial, as well as institutions across the world including the Geffen Contemporary at MOCA, LA, the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney, and the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Denmark. ‘I like the fine art world because it’s a protected space where you can bring all the disciplines together,’ she says.

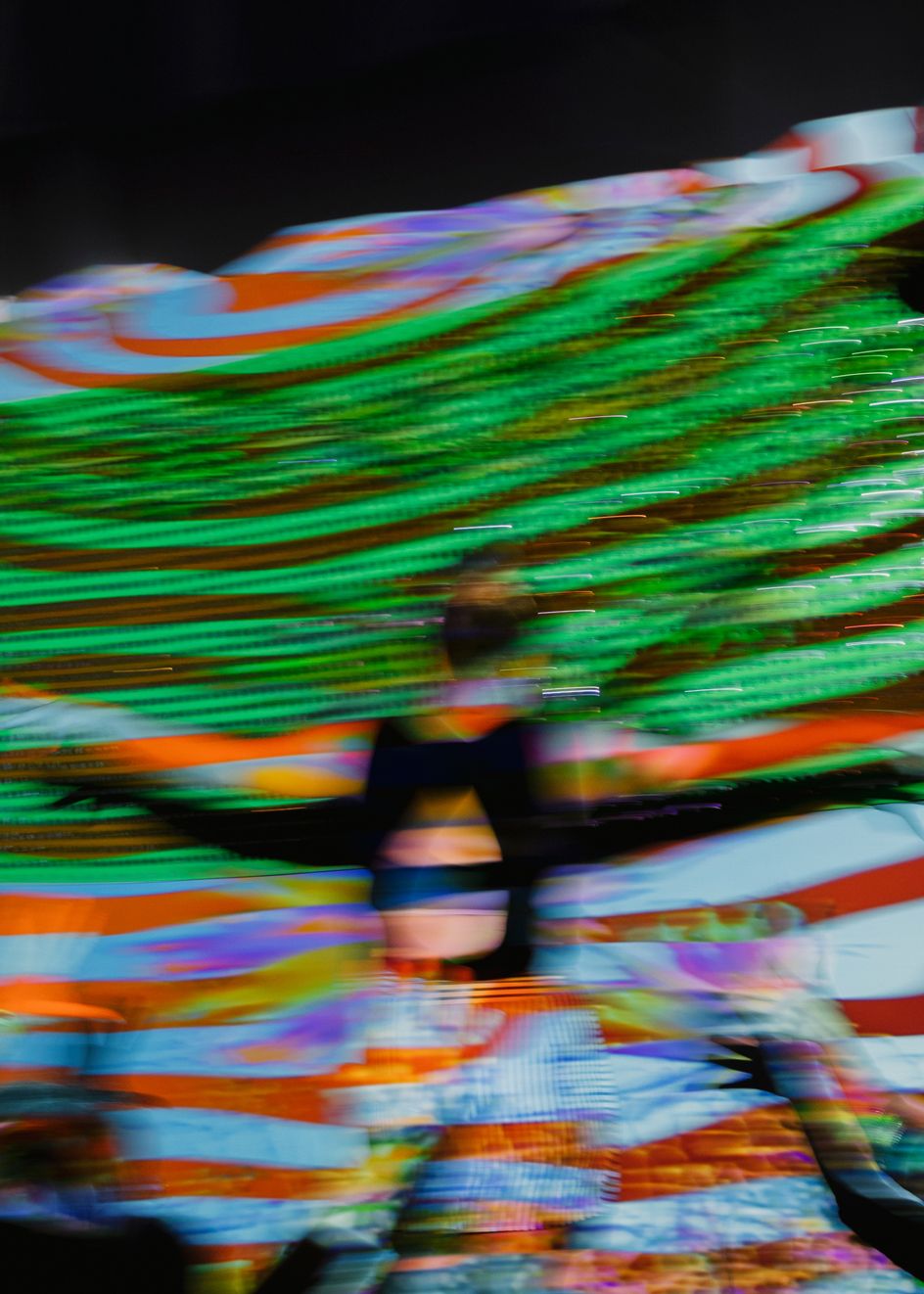

This month’s limited-edition cover features an installation detail of Pipilotti Rist’s Planetenstaub neun neun (grün) (Planetary dust nine nine (green)), (2022), comprising a circular LCD screen with a hood of poured polycarbonate. Limited-edition covers are available to subscribers.

Manuela Wirth, co-founder of Hauser & Wirth, has represented Rist since 1997. She describes the artist as a ‘guiding light’ for the gallery: ‘Pipilotti has expanded my understanding of how art can engage, entrance and immerse everyone – regardless of age or art knowledge.’ Marc Payot, partner and president of Hauser & Wirth, concurs, ‘The miracle of Pipilotti Rist is that she uses the camera with the same impact that the greatest painters have achieved with a brush. Where the first generation of artists working in video – such as Bruce Nauman – did so in relation to the medium’s limitations, Pipilotti set video free. She recreated it and opened a whole new form of expression, an ingenious cosmos all her own. But at the same time, her work is brimming with so much generosity that it engages every kind of viewer.’

Rist’s practice has developed in tandem with technological advancements, and today incorporates large video projects, digital manipulations and ambitious installations. But in the mid-1980s, creating and editing video was a decidedly analogue process. ‘I always was an early adopter. My goal was to squeeze the most out of these machines. Every screen has a different character. That’s something as a video artist I have to deal with,’ says Rist, who has the rare ability to tease humanistic elements from digital art – her work never feels cold. ‘The souls of the ones who have invented these machines are always there. I remember going to Osaka to visit the Panasonic headquarters – it was almost a religious feeling to go where video projection was invented.’ In spite of her reverence for technology, the artist is careful not to let it completely dictate her artistic practice. ‘Today, we are spoiled and expect a higher resolution – that’s why our brain can’t fill in the missing gaps anymore,’ Rist says. ‘But of course, our feelings take up more space. That’s why a painting often can have more reality or more truth in it than a very sharp image, because it gives more space for our interpretation. Extreme sharpness limits the emotional impact you can transport.’

Pipilotti Rist photographed in her Zurich studio.

Rist’s boundary-busting works seem most at home outside of white cube spaces – the light installation Seelenlichter (Soul Lights) (2021), which transformed a Gstaad chalet into a technicolour lantern, and Het leven verspillen aan jou (2022), a video projection in the square surrounding Rotterdam’s Depot Boijmans Van Beuningen, come to mind, as does Jordlys og pingpong med solen (Earthlight and Ping-Pong with the Sun) (2020), a permanent installation for the Danish School of Media and Journalism in Aarhus involving four projections, multicoloured curtains and a large disco ball. Such projects, the artist explains, come with their own set of challenges. ‘Creating work for public spaces requires compromises: from considering weather conditions to a certain limitation of expression.’ Still, ‘a moving image is more difficult to ignore.’ She cites the kaleidoscopic intervention she created in 2011 for the Jean Nouvel-designed Sofitel Vienna Stephansdom as an example where she had to make creative concessions to cater to the hotel’s clientele as well as passers-by. ‘Museums are an ideal space because people take their time,’ she says, before adding that a playground would be her dream canvas for an artistic intervention.

In 2021, the Kunsthaus Zürich inaugurated its David Chipperfield Architects-designed extension with a genre- and era-spanning array of art, including Rist’s Pixel Forest (2021). The installation is on loan from art collector Werner Merzbacher, a Holocaust survivor who fled to Switzerland after his parents were murdered in a concentration camp. ‘He wanted visitors coming to see his collection to go through something that celebrates the underestimated power of colours – he would always say that colour saved his life,’ Rist explains of Merzbacher who, along with his wife Gabriele, has built an extraordinary collection of modern art masterpieces unified by energetic brushwork and bold hues.

Inside the artist’s Zurich studio.

The healing power of art is a quiet thread in Rist’s practice and it’s little wonder that her dazzling visual displays resonate with viewers on a deeper emotional level, even subconsciously. ‘I received a letter from a psychiatrist saying she had sent one of her heavily depressed patients to visit Pixel Forest. The patient said that for the first time in months, she felt a spark of joy,’ recalls Rist. ‘When somebody has depression, it’s less important to know why the ship has sunk, but rather how the ship can come up again.’

Sometimes the connection to mental health is more overt. Earlier this year, the National Museum of Qatar unveiled Rist’s first installation in the Middle East, Your Brain to Me, My Brain to You, in collaboration with the Ministry of Public Health. Visitors are invited to navigate 12,000 resin-encased LED lights – each representing neurons firing and communicating with one another – that have been programmed to sync with a video installation featuring abstract footage of the Qatari landscape. ‘Every day, I am astonished at the resilience of the minds of others – how much we hurt and then go on, and also accept that everyone is hurt,’ says Rist, who practises autogenic training (a relaxation technique) to keep her own mind balanced. ‘I am convinced art can help mental wellbeing; just a moment where you can forget your problems relaxes your brain. Going to a museum is a ritual and can have a calming, comforting effect.’

It’s only fitting, then, that the artist has been invited to create a permanent work at the New North Zealand Hospital in Hillerød, Denmark. Due to be completed in 2024, the clover leaf-like design by Herzog & de Meuron has a garden at its centre, where Rist’s projected installation will take shape. ‘We are working closely with the gardener to either shine through [the plants] or use them as the backdrop,’ she explains, likening the forthcoming work (which will light up for around ten minutes at night) to a ‘bonfire’.

No wonder I walked away from my time with Rist feeling energised and renewed – she’s a feel-good tonic in human form. By pulling us close into her chromatic orbit, Rist brings a big and brilliant picture into view.

Pipilotti’s world: explore the artist’s portfolio for Wallpaper*

In Pipilotti Rist’s world, all things are bright and beautiful. Bed down and admire aquatic life, lose yourself in a forest of LED lights, gaze upon illuminated clothing lines, and dance against a backdrop of vivid projections and architectural spaces. By opening our eyes to the weird and the wonderful, Rist brings us closer to nature – and to one another.

All artworks below, courtesy of Pipilotti Rist, Hauser & Wirth and Luhring Augustine

Pipilotti Rist, 4th Floor To Mildness, 2016 installation view MCA Sydney, photography: Anna Kucera, graphic design: Mariko Okazaki

色とりどりの幽霊, (Multicoloured Ghost), 2021, video still

水虎彩膏, (Water Tiger Color Balm), 2022, installation view Prison Yard, Tai Kwun. Contemporary, Hong Kong

Left: Hiplights, 2011 installation view Hayward, London, photography: Andrew Bulhak; Right: Caressing Dinner Circle, 2017 installation view MCA Sydney

Centre: Neighbors Without Fences, 2021, video still. Behind: Pixelwald Mutterplatte (Pixel Forest Motherboard), 2016 installation view 2022 Tai Kwun Contemporary, Hong Kong

Left: 保護我們免受雨淋 (Protects Us From Rain But Not From...), 2022 installation view Dollhouse, Tai Kwun Contemporary, Hong Kong; Right: Eindrücke verdauen (Digesting Impressions), 1993/2019 installation view 2022 Tai Kwun Contemporary, Hong Kong courtesy of Stiftung Kunst Heute, Kunstmuseum Bern; Behind: Toi Comme Le Corail Symbiotique (You As The Symbiotic Algae), 2018 video performance for WWF Switzerland

タカエズ・トシコに捧ぐダブル・ビッグ・リスペクト (Double Big Respect to Takaezu Toshiko), 2021 MoMAK Kyoto, photo montages: Thomas Rhyner

Het leven verspillen aan jou (Wasting Life on You), 2021 installation view Depot Boijmans van Beuningen, Rotterdam

INFORMATION

A version of this article headlines the November 2022 Art Special Issue of Wallpaper*, available in print, on the Wallpaper* app on Apple iOS, and to subscribers of Apple News +. Subscribe to Wallpaper* today (opens in new tab).

Pipilotti Rist, ‘Behind Your Eyelid’ is on until 27 November at Tai Kwun, Hong Kong, taikwun.hk (opens in new tab), hauserwirth.com (opens in new tab)

-

Year in review: top 10 stories of 2022, as selected by Wallpaper’s Jonathan Bell

Year in review: top 10 stories of 2022, as selected by Wallpaper’s Jonathan BellTop 10 transport stories of 2022, from minimalist motor cars to next-generation campers: transport editor Jonathan Bell’s picks

By Jonathan Bell • Published

-

‘When We See Us’: Black figurative painting at Cape Town’s Zeitz MOCAA

‘When We See Us’: Black figurative painting at Cape Town’s Zeitz MOCAAA group show of Black figurative painting at the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa, featuring 156 artists, explores the past and present of self-representation

By Sean O'Toole • Published

-

Cara \ Davide is the Milanese design duo inventing a new design language on the cusp of contemporary and ancestral

Cara \ Davide is the Milanese design duo inventing a new design language on the cusp of contemporary and ancestralIn our Future Icons series, we explore ten next-generation designers who have made us sit up and take notice: here, we speak to Cara \ Davide about their design process and their cross-cultural inspirations

By Maria Cristina Didero • Published

-

Cerith Wyn Evans: ‘I love nothing more than neon in direct sunlight. It’s heartbreakingly beautiful’

Cerith Wyn Evans: ‘I love nothing more than neon in direct sunlight. It’s heartbreakingly beautiful’Cerith Wyn Evans reflects on his largest show in the UK to date, at Mostyn, Wales – a multisensory, neon-charged fantasia of mind, body and language

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith • Published

-

Art hub Casa Neptuna pops from the Uruguay landscape

Art hub Casa Neptuna pops from the Uruguay landscapeFundación Ama Amoedo announces 2023 art residencies hosted at Casa Neptuna, a space designed by Argentine artist Edgardo Giménez in José Ignacio, Uruguay

By Hannah Silver • Published

-

Enter the mesmerising, AI-driven world of artist Refik Anadol

Enter the mesmerising, AI-driven world of artist Refik AnadolRefik Anadol’s masterly use of data sets and AI models allows him to create dazzling ‘living paintings’, now on display in MoMA’s Gund Lobby

By TF Chan • Published

-

The best 7 Christmas installations in London for art lovers

The best 7 Christmas installations in London for art loversAs London decks its halls for the festive season, explore our pick of the best Christmas installations for the art-, design- and fashion-minded

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith • Published

-

Generative art: the creatives powering the AI art boom

Generative art: the creatives powering the AI art boomIt’s a new age for generative art, thanks to pixel-sorting, algorithm-sifting creatives. While the NFT market remains in flux, we delve into the rise of generative art, and the AI art boom

By Nick Compton • Published

-

Daniel Gebhart de Koekkoek’s 2023 calendar is filled with flamboyant dog portraits

Daniel Gebhart de Koekkoek’s 2023 calendar is filled with flamboyant dog portraitsFor his 2023 calendar, photographer Daniel Gebhart de Koekkoek turns his lens on flamboyantly preened, catwalk-ready dogs, and we’re barking mad for it

By Sophie Gladstone • Published

-

London art exhibitions: a guide for this week

London art exhibitions: a guide for this weekYour guide to the best London art exhibitions, and those around the UK, as chosen by the Wallpaper* arts desk

By Harriet Lloyd Smith • Last updated

-

Monica Bonvicini ‘I do You’ review: bondage, mirrors and feminist takes on masculine architecture

Monica Bonvicini ‘I do You’ review: bondage, mirrors and feminist takes on masculine architectureEmily McDermott reviews Monica Bonvicini’s much-anticipated exhibition ‘I do You’ at Berlin’s Neue Nationalgalerie

By Emily McDermott • Published