A glimpse inside the strange and secretive world of Serge Lutens

Serge Lutens – whose career encompasses fragrance, beauty, photography and film – has launched his first home fragrance collection. To mark the launch, we tour Lutens’ sprawling Marrakech foundation, a kaleidoscopic complex of beautifully decorated riads

- (opens in new tab)

- (opens in new tab)

- (opens in new tab)

- Sign up to our newsletter Newsletter

The mirrors in Serge Lutens’ home-turned-foundation in Marrakech are sliver-thin, so you can only see fractions of yourself inside them. They are an apt reflection of Lutens, who likes to speak about the multifarious nature of human beings. ‘We have multiple people inside us,’ he says. ‘That’s what makes us so rich, and what’s surprising about meeting people; to identify these different facets, what their character is built on, how it is shaped.’

To meet Lutens is to discover a man with many, often conflicting, facets. A man who, since 1974, has been building a home to rival any palace in its opulence and beauty, yet which remains largely empty and rarely accepts visitors. A figure routinely lauded as one of the most influential figures in the beauty industry – for his iconoclastic approach to make-up, his subversive campaigns and editorial imagery, and his groundbreaking cosmetic lines – who has spent the past few decades living as a recluse in Morocco.

A person so secretive that he largely refused interviews until recently, but will readily reveal deeply personal and painful aspects of his past. A man so shy that he avoids round spaces, finding them too revealing, preferring to ‘hide’ in corners, yet, when you meet him, is a beacon of warmth and charm, playfully self-deprecating, utterly captivating.

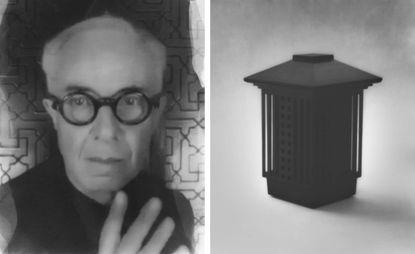

Incense holder from the Serge Lutens home fragrance collection.

Born out of wedlock in Lille, France, in 1942, Lutens is, as he puts it, ‘a biological accident’. His mother had to put him into foster care a few weeks after his birth. Lutens speaks openly about how the separation shaped the rest of his life, making him feel ‘always on the margins, a misfit’, and propelling him to find refuge in his own fantasy world. He says of the circumstances of his birth: ‘We will be obsessed with this story our whole life. We will try to transcend that story, to destroy it. But it belongs to us. It’s part of our body, part of our skin. Everything is right there and it will never leave us.’

When Lutens was 20 years old, he relocated to Paris, submitted some photographs to Vogue, and set the course for one of the most illustrious editorial careers of the 1960s and 1970s. He achieved renown as an industry ‘multi-hyphenate’ and ‘polymath’ long before those terms achieved their present-day ubiquity; art directing, photographing and styling all of his own imagery for publications such as Vogue, Elle, Harper’s Bazaar and more.

By that point, he had already established his signature aesthetic: models in nondescript spaces wearing ghostly foundation, extreme eye make-up, graphically painted lips, vinyl hair, and a lot of black (his trademark colour), creating hypnagogic visions of women caught between times and realities – a little bit kabuki, a little bit Weimar, a dash of 1940s Hollywood, an echo of art deco.

Serge Lutens preparing one of his models, Isabelle Weingarten, for one of the photoshoots in the Make-up Art series, an exhibition dedicated to Serge Lutens’ work, presented at the time at the Guggenheim Museum in New York.

In 1968, when he was 26 years old, Lutens became the image director for Dior Beauty, creating its first fully-fledged make-up line and overseeing every creative aspect, from make-up colours to editorial images. But the apex of Lutens’ career came with his appointment to Shiseido in 1980, which offered him abundant freedom and resources to create some of the most memorable commercial imagery of the late 20th century. In turn, he transformed the brand from an entity little known outside Japan into an industry titan.

Lutens’ impact on the beauty industry cannot be overstated. His work at Dior laid the foundation for how luxury brands would develop and market beauty ranges. At Shiseido, he informed a style of beauty advertising that survives today. Meanwhile, his eponymous cosmetic line, launched in 2000, is a highly edited toolkit for Lutens-esque beauty, with lipsticks in purples and reds, a variety of primers for creating immaculate skin, and precision eyeliners.

Key players in today’s beauty industry that cite him as an influence include Isamaya Ffrench, who, through her work with brands such as Byredo (opens in new tab) and Burberry, has pioneered her own disruptive vision of beauty. ‘Serge Lutens was the first person to be a make-up artist on top of being a multidisciplinary artist,’ she says. ‘I recommend anyone who’s not familiar with his work to watch the ads he created for Shiseido’s Inoui line. His work was not a way to document make-up, it was a whole artistic vision, extremely painterly, intriguing and timeless.’

Continuing on Ffrench’s sentiment, make-up artist Lisa Eldridge says: ‘It’s hard to define Serge Lutens, but true to say that he’s one of the most inspiring beauty visionaries of all time. I’ve always admired his incredibly powerful, magical and provocative style, and was greatly honoured to follow in his footsteps back in the early 2000s when I worked as the creative director for Shiseido. One of my favourite things to do was to visit the archives to look through all of his work.’

‘Modigliani’ by Serge Lutens, 1972. Photograph by Serge Lutens, inspired by painter Amedeo Modigliani’s portraits. This image is also part of the photography series that Serge Lutens dedicated to key 20th century painters. To ensure his tribute was as accurate as possible, Serge Lutens had a pair of contact lenses made for the model, so that her eyes would look like the lifeless eyes of characters in most of Modigliani’s portraits.

US Vogue editor-in-chief Diana Vreeland called Lutens a ‘revolution of make-up’ in a 1974 issue because he subverted the idea that cosmetics were for ‘improving’ a woman’s appearance; instead, he used make-up as a tool for reconfiguring the human face into new extremes that challenged prevailing beauty orthodoxies.

Thanks to Lutens, glossy editorials and ads suddenly depicted women differently: a model with pencil-thin eyebrows staring into the camera through completely black, narrow eyes; or a ghoulish woman wearing a black leather jacket, her lavender-shadowed eyes partly open, while a plume of blue smoke escapes from her burgundy lips.

Like a cosmetic psychoanalyst, Lutens used these images to plumb the depths of our fears and fantasies. ‘I think life is about chaos and something that we fear. We can change our lives,’ he says. ‘That’s what beauty is about, and to define it, basically, is to betray it. Beauty is there to get us out of our comfort zone, our personal boundaries, even our dislikes.’ The resulting images are as affecting today as ever. ‘His images are always at the back of my head because they’re so unique,’ says Ffrench. ‘His make-up approach was integrated in a bigger picture. His women are ethereal, mysterious, almost haunting, but always incredibly beautiful. I admire that balance.’

'Qué Seurat Seurat’ by Serge Lutens, 1972. Lutens was inspired by the pointillist style of painter Georges Seurat. When it was released, this image was used as the official poster for the Make-up Art exhibition.

Lutens’ most ardent passion these days is fragrances. He launches his first home collection this year, five scents inspired by five different locations – the Moroccan house, Moroccan garden, Japanese house, Scottish house, and a linen cupboard – and available as a home spray, incense with a holder shaped like a black wisp of smoke, and a pagoda-like diffuser. Lutens notes that variety and, uncharacteristically for him, subtlety, were important for this collection.

‘A home scent must serve your home,’ he says. ‘I don’t like smells that feel like they’ve been added to the house. For example, I think it is a nightmare when people use lavender to hide the smell of onions, or use scented paraffin candles to scent a home – it’s dirty, it stinks, it distorts perfume, it kills perfume. For me, a house has an identity and I’m interested in its character, not it doing something else.’

The Serge Lutens Foundation

Lutens creates all of his fragrances in a lab inside the Serge Lutens Foundation, the more than 3,000 sq m complex he has built in Marrakech. This, perhaps more than any of Lutens’ creations, is the most exquisite crystallisation of his unique vision, a dreamscape that simultaneously recalls Borges’ labyrinths, Dracula’s gothic palace, and the opulence of Huysmans’ À Rebours.

The foundation is in the heart of the city, down an old narrow street, past donkey-drawn carts and cars skilfully manoeuvring tight curves made by buildings of washed stone, and vendors selling everything from produce to carpets behind open arched doorways. Its black door looks unassuming enough, but step behind it and the sensorial torrent of the outside world is instantly and dramatically quelled.

Serge Lutens inside one of the narrow hallways of the Serge Lutens Foundation.

A dark atrium lets in no natural light, but what little illumination there is from chequer-sized lights or narrow stained glass windows makes it possible to see that every inch of the room is decorated in patterns and textured materials. It is a maze of endless rooms and narrow hallways that feels intimate and mysterious, like the sombre melancholy of an empty cathedral.

Lutens has designed everything in the space, from the abstract patterns that decorate the walls to the furniture that fills the rooms. Everything is in keeping with his style of sumptuous eeriness. There are black chairs with backs that resemble cathedral windows; red velvet settees embossed with intricate geometric patterns that are reflected on the ceiling; and hefty black tables covered in curios, such as a dried elephant foot and wooden masks.

It feels like stepping inside a kaleidoscope, with every turn revealing a prismatic array of textures, patterns and objects. The effect is hallucinatory, to the extent that, after an hour of walking around, I glance down at the black-and-white floor and I swear for a brief moment it is levitating.

One of the gardens at the Serge Lutens Foundation.

Ushered into one of the house’s cloistered gardens for lunch (and still having only seen a fraction of the foundation), the natural light arrives with a jolt. No doubt, Lutens has designed it this way, to create the sensation of exiting the womb-like interiors to be birthed into the light. When I take a sip of a bubbly brown liquid served from a horn- shaped decanter, I’m shocked to find it is Coca-Cola. By this point, anything so normal feels like an anomaly, a relic of a place we have long since left behind.

There is a multi-room hammam, with bathtubs and faucets, there are tea and cutlery sets, also designed by Lutens. Yet nothing is ever used and few people ever see it.

‘This house is a story of my childhood, a story of my life,’ he says. ‘I bought it in 1974 when I was having a nervous breakdown. When you are in a bad condition, you need to set one single goal, and then you hang on to it. Otherwise, you would just collapse. So I thought, I’m going to buy a house – that’s it. I visited many, many houses... [When] I had only three days left before going back to Paris, an old man in the street, all dressed in white, grabbed my arm and said, ‘I know what you’re looking for, come with me.’

Lutens was taken to a house in ruins, but he ‘immediately felt something... and thought that’s it. That’s the place.’ He moved in briefly but soon felt that the house was ‘rejecting me, pushing me away’. But he did not give it up. Instead, what was planned as a four-month renovation of a single house became a 58-year-long project comprising multiple homes and, with the recent purchase of ten new riads to add to the complex, no signs of finishing soon.

One of the libraries in the Serge Lutens Foundation illuminated and photographed.

Lutens concedes he doesn’t really have an ultimate plan for this remarkable, fanatical project. He created the foundation solely for himself, which is part of the reason he has kept it so secret. Yet, he also believes that ‘it belongs to Morocco and no one else’, and suggests that when he dies he will bequeath it to the country. Death is something that seems to play on Lutens’ mind. Over the course of our conversation, I get the impression of a man spending a lot of time looking back.

‘Life goes fast, it goes very fast,’ he says. ‘For a long time, I lived without even knowing it, because I was just enjoying what I did. So I lived, but through other things.I didn’t look to myself to find this idea of happiness because it is absurd. Seeking happiness is basically never finding it, because it is a preconceived idea. It doesn’t work. You can experience some nice moments, but it is not a goal in itself to be happy.’

‘I’ve lived most of my life,’ he continues. ‘I’m 80 years old, so I have some time left, but I know it is unusual to still be here at this age. It is not bad when everything is all right enough in your head that you can build sensitivity through reading, through the people you meet. It is still great to explore, to know you will become intellectually and spiritually richer, and nothing is ever finished until it is really finished.’

INFORMATION

A version of this article appears in the October 2022 issue of Wallpaper*, available in print, on the Wallpaper* app on Apple iOS, and to subscribers of Apple News +. Subscribe to Wallpaper* today!

sergelutens.com (opens in new tab)

Mary Cleary is the Beauty & Grooming Editor of Wallpaper*. Having been with the brand since 2017, she became an editor in February 2020 with the launch of the brand’s new beauty & grooming channel. Her work seeks to offer a new perspective on beauty, focusing on the pioneering personalities, product designs, and transformative trends within the industry.

-

34th São Paulo Bienal arrives at Luma Arles for first European presentation

34th São Paulo Bienal arrives at Luma Arles for first European presentationAn exhibition of highlights from the 34th São Paulo Bienal is at Luma Arles, marking its European and tour finale

By Martha Elliott • Published

-

This winter’s most stylish skiwear, Gucci to Hermès

This winter’s most stylish skiwear, Gucci to HermèsStatement-making skiwear for on and off the slopes, from Louis Vuitton, Dior, Moncler and more

By Jack Moss • Published

-

Clásicos Mexicanos celebrates Mexican design’s golden age

Clásicos Mexicanos celebrates Mexican design’s golden ageDesign Miami 2022: the Maestro Dobel Artpothecary in collaboration with Clásicos Mexicanos features works from Mexican architect Ricardo Legorreta’s ‘Vallarta’ collection

By Sujata Burman • Published

-

New Cartier fragrance laboratory recalls a chic Parisian apartment

New Cartier fragrance laboratory recalls a chic Parisian apartmentCartier perfumer Mathilde Laurent unveils her art- and design-filled fragrance laboratory in Paris

By Mary Cleary • Last updated

-

The best perfumes for women take a cue from history

The best perfumes for women take a cue from historyThe best perfumes for women look to both historical and fictional figures to inspire their inclusive take on femininity. We share our selects here

By Mary Cleary • Last updated

-

Diptyque’s classic florals blossom into digital bouquets

Diptyque’s classic florals blossom into digital bouquetsDiptyque reimagines its signature floral fragrances through the work of digital floral artist Bas Meeuws

By Mary Cleary • Last updated

-

Seeing scent: the moodboard behind DS & Durga's new fragrance

Seeing scent: the moodboard behind DS & Durga's new fragranceThe New York perfumers give us an exclusive peak at the images that inspired their latest fragrance enhancer, ‘Crystal Pistil'

By Mary Cleary • Last updated

-

Elegantly bottled perfumes hitting the right notes

Elegantly bottled perfumes hitting the right notesOur edit of the superior scents that are just as easy on the eye as they are on the nose, from Celine, Nars and Ormaie

By Emi Eleode • Last updated

-

Hedi Slimane knows what he nose in Celine’s Paris perfume boutique

Hedi Slimane knows what he nose in Celine’s Paris perfume boutiqueThe artistic director unveils his new fragrance collection for Celine with a perfume boutique in Paris

By Tilly Macalister-Smith • Last updated

-

Exploring non-binary beauty at Dover Street Parfums Market in Paris

Exploring non-binary beauty at Dover Street Parfums Market in ParisBy Fiona Mahon • Last updated

-

A trio of prize perfumes on a pedestal wins Wallpaper* Design Award

A trio of prize perfumes on a pedestal wins Wallpaper* Design AwardBy Emma Moore • Last updated