The most surreal moments in Art Basel history, from taped bananas to wealth-ranking ATMs

As a wealth-ranking ATM stole hearts and headlines at Art Basel Miami 2022, we look back on the most controversial moments in the history of Art Basel

- (opens in new tab)

- (opens in new tab)

- (opens in new tab)

- Sign up to our newsletter Newsletter

Art Basel was founded in 1970 to lure a new wave of collectors and enthusiasts in the postwar consumer society, rich in time, money and new means of global communication. The art mega fair has spent the last 50 years redefining what an art event can be. Beyond a marketplace for the deep-pocketed, a magnet for celebrities, a hotbed for lavish parties and fertile ground for people-watching, Art Basel has become a cultural incubator for some of the most radical moments in the history of contemporary art.

Following an epic Art Basel Miami 2022, we take the opportunity to reflect on the unforgettable moments that have defined the fair’s history, from taped bananas to wealth-ranking ATMs.

An ATM displayed and ranked visitors’ bank balances

MSCHF, ATM Leaderboard, 2022

How would you feel to see your bank balance displayed, and ranked, in public? Well, it might depend on how much you had in there. At Perrotin’s booth at Art Basel Miami 2022, American art collective MSCHF debuted ATM Leaderboard, an installation displaying the real-time bank balances of users (with a picture of their faces), and ranking them in order of wealth.

Monster Chetwynd played ball on Art Basel’s Messeplatz

Monster Chetwynd, Tears, Messeplatz 2020

At Art Basel 2021, British artist Monster Chetwynd made quite the entrance. Taking to the Messeplatz near the fair entry point, performers clad in glamorous, sequin-studded costumes rolled in and danced around giant transparent zorbs directed by the artist’s choreography. This extraterrestrial performance, titled Tears, was inspired by Salvador Dalí’s bejewelled crying eye timepiece and made for a poetic, absurd and jaw-dropping prologue to Art Basel’s 2021 edition.

Maurizio Cattelan’s duct tape-meets-banana drama

Maurizio Cattelan, Comedian, taped to the booth wall of Perrotin gallery at Art Basel Miami Beach, 2019

In 2019, it had been a while since the art world had given its community an electric shock. Just as the dust was settling (in retrospect, the calm before an earth-rattling storm), Maurizio Cattelan took the lull as an opportunity to strike. Created in an edition of three, his Comedian consisted of a fresh – if lightly bruised – solitary banana taped to Perrotin gallery’s booth wall with a piece of metallic duct tape. It was a minimal composition – which later inspired a series of T-shirts – using a classic comedy device to comment on global trade. Or maybe not; as Cattelan put it, ‘The banana is supposed to be a banana’.

An Art Basel visitor gets a closer look at Comedian, which was subsequently eaten by Georgian performance artist David Datuna

In another dramatic plot twist, Georgian performance artist David Datuna ate the piece, calling his post-sale intervention Hungry Artist. This was not the first time Cattelan had harnessed this lucrative combination of tape, walls and organic matter. Twenty years previously, the artist adhered his gallerist, Massimo de Carlo, to his gallery wall in Milan in a web of electrical tape. De Carlo, like the banana, found himself at the complete mercy of the artist in a piece that gave new meaning to the notion of ‘bonding’.

Klaus Biesenbach and Hans Ulrich Obrist got a room, well 14 Rooms

14 Rooms, a group piece at Art Basel (Basel) 2014, featuring work by 14 international artists and organised by Klaus Biesenbach and Hans Ulrich Obrist

14 Rooms, to some extent, was what it said on the tin. For the live artwork, curatorial powerhouses Klaus Biesenbach and Hans Ulrich Obrist invited 14 international artists to each ‘activate’ a room, examining the relationship between space, time, and physicality. But, as one might imagine, there was a twist: each artwork’s ‘material’ was a human being.

Luminosity (1997). Part of 14 Rooms, Art Basel, 2014. Presented by Fondation Beyeler, Art Basel and Theater Basel

The piece sat somewhere between theatre, sculpture and museum exhibition. The commission was of unprecedented scale for an art fair, running the full duration of Art Basel. This edition of the piece, which first premiered at Manchester International Festival as 11 Rooms, featured works by Marina Abramović, Damien Hirst, Santiago Sierra, Xu Zhen, Ed Atkins, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, and Otobong Nkanga, the latter three debuting new works. Each work took place within its own closed-off room, designed by architects Herzog & de Meuron.

Art Basel braved a new virtual reality

Antony Gormley, Breathing Room II, 2010. Aluminum tube 25 x 25 mm, Phosphor H15, and plastic spigots, 386 x 857 x 928 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Galleria Continua.

Before 2020, the term ‘OVR’ might have sounded more like an obscure business acronym, or possibly an obsolete file format. But when Covid-19 struck, it became a lifeline for the globally art-deprived. OVRs (Online Viewing Rooms), came to the fore following the outbreak of Covid-19. In the year of its 50th anniversary, Art Basel had no option but to cancel the 2020 edition of Art Basel Hong Kong. As the first major domino to fall, this sent shockwaves through the art world and left all subsequent in-person events in a frenzy of uncertainty. To keep the momentum alive, Art Basel recalibrated with the first digital-only edition.

Kader Attia smashed up his Arab Spring installation

Kader Attia smashes up his Arab Spring (2014) installation at Art Basel Unlimited, 2015, Galleria Continua

It was a 2011 press image of looted glass vitrines in Cairo's Egyptian Museum that inspired Kader Attia’s Arab Spring (2014). For the sculptural installation, staged at Art Basel Unlimited in 2015, Attia re-enacted the moment protesters entered the museum, destroyed its display cases, and robbed their contents during the Arab Revolutions of 2011-12.

Kader Attia, Arab Spring (2014) at Art Basel Unlimited, 2015, Galleria Continua

Attia wears a dark hoodie shielding his face as he pelts bricks to shatter the vitrines – a gritty performance, filled with revolt and anger. In Arab Spring, Attia explored the legacy of colonialism, specifically French colonialism, and the contradictory notion of how a country intent on reclaiming its future would destroy what was at last becoming theirs. Attia staged the performance at the preview of Art Basel, the shattered glass and red brick debris forming the final work.

INFORMATION

Harriet Lloyd-Smith is the Arts Editor of Wallpaper*, responsible for the art pages across digital and print, including profiles, exhibition reviews, and contemporary art collaborations. She started at Wallpaper* in 2017 and has written for leading contemporary art publications, auction houses and arts charities, and lectured on review writing and art journalism. When she’s not writing about art, she’s making her own.

-

2022 fashion highlights, as picked by the Wallpaper* team

2022 fashion highlights, as picked by the Wallpaper* teamThe Wallpaper* fashion and beauty team reflect on their personal 2022 fashion highlights – from Gaetano Pesce at Bottega Veneta and Wales Bonner in Florence to intrigue and seduction at Prada

By Jack Moss • Published

-

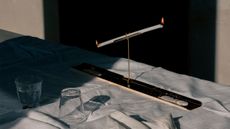

Marre Moerel’s swinging flame candle uses artful balance

Marre Moerel’s swinging flame candle uses artful balanceVita Balanza by Marre Moerel and Santa & Cole has turned candles into a balancing act

By Martha Elliott • Published

-

At home with Neri & Hu

At home with Neri & HuArchitectural super-pair Neri & Hu talk to us about what inspires them, what they are reading, and how they switch off

By Ellie Stathaki • Published

-

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s Pulse Topology in Miami is powered by heartbeats

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s Pulse Topology in Miami is powered by heartbeatsRafael Lozano-Hemmer brings heart and human connection to Miami Art Week 2022 with Pulse Topology, an interactive light installation at Superblue Miami in collaboration with BMW i

By Fiona Mahon • Last updated

-

Miami Art Week 2022: your guide to the 6 best shows in town

Miami Art Week 2022: your guide to the 6 best shows in townAs Miami Art Week 2022 enters full swing, explore our preview guide to the highlights, from Art Basel Miami Beach 2022 art fair to the best exhibitions and events

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith • Last updated

-

Artissima 2022: art exhibitions to see this weekend in Turin

Artissima 2022: art exhibitions to see this weekend in TurinTurin art fair Artissima 2022 spans the experimental and the perspective-bending; here’s what to see

By Martha Elliott • Published

-

Alicja Kwade’s installation ‘brings the stars down’ onto Place Vendôme

Alicja Kwade’s installation ‘brings the stars down’ onto Place VendômePolish-German artist Alicja Kwade has adorned Place Vendôme with an interactive installation comprising natural stone spheres and concrete stairs, as part of the Paris+ par Art Basel ‘Sites’ project

By Flora Vesterberg • Last updated

-

Paris+ par Art Basel: how the new art fair could transform Europe’s cultural identity

Paris+ par Art Basel: how the new art fair could transform Europe’s cultural identityWallpaper* Paris editor Amy Serafin explores the inaugural edition of Paris+ par Art Basel and speaks to key figures about what the new art fair will mean for Europe’s art scene

By Amy Serafin • Last updated

-

Step inside the kaleidoscopic universe of Pipilotti Rist

Step inside the kaleidoscopic universe of Pipilotti RistSwiss artist Pipilotti Rist, who headlines Wallpaper’s November 2022 issue, has transformed the way we see, with a poetic yet playful practice spanning three decades. Here, and in a special portfolio, she reveals how she has liberated video art from its conventions, imbued the digital realm with emotion, animated public spaces, and harnessed the healing powers of colour

By Jessica Klingelfuss • Last updated

-

Olivia Arthur on expanding photography and minimising preconceptions

Olivia Arthur on expanding photography and minimising preconceptions‘Through the lens’ is our monthly series that spotlights photographers who are Wallpaper* contributors. Here we explore the vision of Magnum photographer Olivia Arthur

By Sophie Gladstone • Last updated

-

Artist Julianknxx on poetry, dreams and Switzerland

Artist Julianknxx on poetry, dreams and SwitzerlandAhead of the New York showing of his major new film with Switzerland Tourism, we visit the studio of London-based poet and filmmaker Julianknxx

By Jessica Klingelfuss • Last updated